Bordeaux, France

Bordeaux City Council

January 2019 - End of 2021

Entire region

To extend the local people’s rights relating to political participation

Bordeaux’s participatory budgeting was implemented with the aim of getting the local people more involved in institutional operation and to reinforce the participatory culture in the city. Although citizen participation and consultation mechanisms already exist in Bordeaux, the aim of participatory budgeting is different in that it encourages the local people to get involved, by inviting them to propose very specific projects that will be carried out by the city. The dynamic of participatory budgeting is reinforced in the voting phase, which gives all the people the opportunity to vote for their three favourite projects. The participatory budgeting policy allowed all the residents of Bordeaux to take part, with no age limit and with no condition of nationality. Hence, foreign nationals living in Bordeaux and youths under age 18 (the full legal age in France), who do not usually have the right to vote, were able to take part in the local life of their region, thanks to participatory budgeting. Moreover, a major communication campaign was launched, to reach as many people as possible.

The numbers of the first round of the experience in Bordeaux are indicative of success:

€2.5 million allocated to participatory budget projects;

407 project proposals;

13,303 voters, accounting for 5% of Bordeaux’s population;

41 projects that were voted on and implemented within a 2-year term.

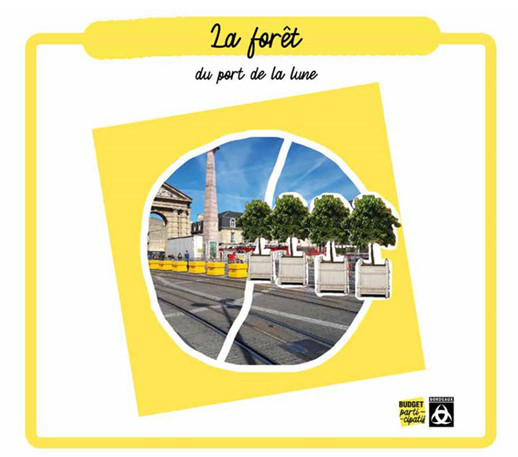

Yet mention must also be made of the quality of the peoples’ proposals. The projects proposed within the framework of the participatory budget are particularly characterised by their great diversity and creativity: the creation of climbing blocks in the city; the installation of beehives; the setting up of a carpentry workshop for everyone to use; the creation of shared gardens, and more.

Participation was equally diversified, including children, students, young workers and retirees, among others.

We have even exceeded our objective, as we have not only created a structure of cooperation between citizens and members of the government, but also a joint citizen cooperative structure.

For the past twenty years, participatory budgeting processes have existed all around the world. The participatory budgeting process in Bordeaux stands out primarily for the personalised support provided to the local people who propose projects. To create a particular dynamic of cooperation among those involved, the participatory budgeting team therefore decided to offer the residents assistance for the draft of their projects. In all, eight workshops were held within each of the city’s eight districts during the project submission phase. A multidisciplinary team was onsite at each workshop to encourage exchanges among the people regarding their different projects, helping them to draw up descriptions of those projects and above all, to create images for their illustration. Given that this work often involved drawing, illustration, computer graphics and collage, those images, which at times were more communicative than a simple text, enabled the participants to specify their projects, while bringing them more to life. Unlike more traditional consultation meetings where the people often come to defend their private interests, these workshops fostered a truly positive co-building dynamic around the projects to be located in Bordeaux’s public space.

Once adapted to the specific features of each group, some of the tools that have led to the development of the process could be partially transferrable: the participatory budgeting policy; the schedule for the project’s different phases; the creation of a monitoring committee (in charge of ensuring the transparency of the procedure during the analysis phase and composed of elected members of the government from the majority and the opposition, and local people selected at random); the negotiation workshops and even the mobile voting station. This need to adapt to the features of each region can be seen, for example in the sites of the 8 negotiation workshops, which were chosen on a case-by-case basis in original locations, to attract different audiences (museum, school, civic centre, etc.). Similarly, the mobile voting station route that ran through the entire city of Bordeaux throughout the voting phase was constructed in keeping with the specific features of each district of Bordeaux (times of its passage, meeting places, cultural habits, etc.).

Moreover, the updated information on the participatory budget was transmitted by the public administrations on several different platforms.

The online platform for the participatory budget presents the participatory budgeting charter, its regulations, its instructions and the composition of the monitoring committee, as well as all the proposed projects and the winning projects. This customizable platform was provided by a private service company that equips many different communities. Information on the progress of the participatory budget was gradually communicated to the members of the government at the monthly Bordeaux Municipal Council meetings, and via the city’s other channels of communication (website, social media). Clearly, one of the most important forms of dissemination was the media coverage following the numerous articles on the subject by the local specialised press.

At the end of 2018, France was overwhelmed by the new social protest model of the yellow vests movement. The people’s disapproval of the institutions and political representatives, and more generally, their dissatisfaction with the democratic system, were among the main complaints. Bordeaux’s participatory budgeting, which was just beginning at that time, displayed a specific and transparent grassroots approach and undoubtedly struck a chord with the people.

Moreover, in the last couple of years, the environmental crisis has become the great challenge of our contemporary democratic societies. In October 2018, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report on global warming further reinforced this awareness. The issue of sustainable development in the Bordeaux participatory budget hence made it possible to respond to a need expressed by the general public and particularly by the people of Bordeaux.

Finally, Bordeaux has been a booming city, both demographically and economically, for the last twenty years. Development projects can be seen all around the city. Participatory budgeting therefore meets the needs of the Bordeaux people to make these new public spaces their own. Because Bordeaux is viewed as a predominantly stone and cement city with little vegetation, the issue of sustainable development revealed the desire of the local people to make their city greener, to mitigate urban heat islands.

The members of the Standing District Committees (SDC) took part in handling the participatory budgeting through the local people. This participatory and consultative level, present in each of the 8 districts, is composed of 20 local residents selected at random and 20 local residents appointed by the Deputy Mayor of the district. The awareness of the members of these SDCs was therefore raised and they received all the relevant information before the launch of this first edition of participatory budgeting, in order to encourage them to propose projects, vote and act as spokespersons for the participatory budget in their respective districts.

On the evening when the participatory budget was launched, all the members of the community were also invited, so that they could disseminate the information on this new system.

Moreover, the dynamic action of the participatory budget intersects with that of the social and territorial cohesion agreement created in 2014, with the aim of converting the new challenges in the region into opportunities through shared and transversal governance.

During the analysis phase to determine which projects would be brought to vote, the Monitoring Committee got all the members of the City Council involved: this included both the political majority and the opposition. Local people selected at random and the contact personnel of the city’s administrative departments were also invited. All of these agents worked together to study the projects; a factor that contributes to the legitimacy of the system. The inclusion of residents selected at random reinforced transparency, while the inclusion of the community services provided the expertise necessary for the development of the projects. Everyone was an agent in this analysis phase and shared the responsibility.

In addition, to carry out the projects, representatives of the city’s different departments were brought in to collaborate with the members of the local community who proposed the projects. Therefore, there was a partnership for each project, composed of the “project leader” (the local resident who initially proposed the project) and a “project manager” (the representative of the relevant municipal department). In all, six different general offices were mobilised.

During the process, the Monitoring Committee was responsible for ensuring the transparency of the assessment of the projects by the city’s departments. The Committee hence assessed the analysis conducted by the technical departments. Each of the three Monitoring Committees was provided with a detailed report. Throughout the process, political monitoring was also the subject of eight reports that were sent to the City Council.

Throughout the entire process, evaluations were carried out by the participatory budgeting team. Questionnaires were submitted to the municipal service agents who had handled the files and to the local people who had participated in this first edition. Additionally, follow-up surveys were conducted to obtain feedback from those involved in the process. Twelve 30-minute interviews were conducted with 2 government officials, 3 municipal service agents, 3 representatives of private service providers and 4 residents. These diverse profiles provided a wide-ranging panorama of experiences, as each agent had been involved at different moments, with different levels of awareness and interest. This report then made it possible to draw up suggestions for development for subsequent editions.

Nevertheless, there is no final evaluation, as the experience is not completely finished. In fact, the development of the awarded projects is still in progress.

The conclusions put forth reveal the genuine enthusiasm of everyone involved regarding the quality of the system. The creativity of the projects, the social connection and even the synergy among the residents are the key elements of this first edition of participatory budgeting in Bordeaux.